Knee Problems: Patellofemoral Disorders

What is Patellofemoral Joint?

The knee joint is made of two main joints: tibiofemoral and patellofemoral. The patella (knee cap), is a mobile, realtively flat, triangular bone within the tendon of the quadriceps muscles, which articulates with the femoral trochlea (groove at the end and on the top of the thighbone).

Patello-femoral joint in motion (click on each image): |

||

The anatomy and mechanics of patellofemoral joint. Source: Primal Pictures Ltd., London, UK. |

||

Anterior Knee Pain

Patients with patellofemoral pain represent a significant challenge to the orthopaedic and rehabilitation community, despite recent advances in the understanding of almost all other knee conditions. This clinical conundrum is often aptly named “The Black Hole of Orthopaedics”, implying that no single explanation or therapeutic approach has yet fully clarified this problem. The primary factor differentiating this clinical problem from other knee conditions is its inherent subjectivity. Anterior knee pain, or patellofemoral pain, is pain in the front of the knee which is often made worse by sitting for prolonged periods, stair climbing or any activity which involves bending the knee. It is often aggravated by sport. The origin of patellofemoral pain can be directly traced to supraphysiological mechanical loading and mechanical or chemical irritation of nerve endings. Even activities of daily living can become supraphysiologic. Studies have shown that the so-called patellofemoral pain syndrome comprises up to 50% overuse injuries. This syndrome is caused by an irritation or damage to the undersurface of the patella, or patellofemoral articulating surfaces, often inappropriately called chondromalacia patella.

What Causes Patellofemoral Pain?

Pure patellar pain remains poorly understood. Articular cartilage lesions themselves are asymptomatic, although the alteration of normal protective compressive stiffness and load-bearing properties of thinned-out or damaged articular surface remains a potential source of pain.

Contributing factors: several anatomical factors like genu valgum (knock knees), abnormal twisting of the femur (femoral torsion), and flat (pronated) feet contribute to the onset of the anterior knee pain. When the patella is not centred in the groove of the femur, there is an imbalance that results in increased pressures between articulating surfaces and subsequent accelerated wear and tear (patella malalignment). Most clinicians subscribe to the concept of patellar malalignment as a source of pain. Abnormal pressure on the patella may result in patellofemoral knee pain. If you are very active and are involved in sporting activities the pressure may be normally placed through the patella but in excessive amounts, an example would be jogging where as much as seven times ones body weight may be transmitted through the knee.Overuse, especially the pounding shocks absorbed during jogging and downhill running, previous knee injuries like the direct blow to the front of the knee, and obesity are all significant contributing factors.

Treatment: nonsurgical management continues to be the mainstay of treatment for Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Historically this has involved strengthening the quadriceps muscle, in particular the vastus medialis obliquus muscle. Currently a more global approach to optimizing function of the lower-extremity kinematic chain is advocated. This can include:

- optimizing the strength of the pelvifemoral musculature to help control limb alignment and rotation;

- optimizing the balance between quadriceps and hamstring muscle strength and firing sequence;

- optimizing the balance between the individual components of the quadriceps muscle bellies, in particular the medial and lateral dynamic stabilizers of the\patella; and

- improving proprioception.

Although these approaches have been shown to be beneficial in alleviating patellofemoral pain syndrome, the relationship between neuromotor control of the knee musculature and the onset/recurrence of symptoms continues to be poorly understood.*

Chondromalacia

The term chondromalacia patellae was introduced into the literature by Aleman in 1928. This word is a misnomer and a source of confusion which should be abandoned. Indeed, the presence of “soft cartilage” – the literal translation of the term chondromalacia – is not strongly correlated with patellar pain. Chondromalacia occurs as the articular cartilage on the back of the patella is damaged. Damaged cartilage can’t distribute pressure evenly along the back of the patella. Damaged articular cartilage can be repaired only partially as normal hyaline articular cartilage can not be reconstructed or replaced as yet.

Arthroscopic manual debridement and power shaving of damaged articular cartilage are common procedures aimed at smoothening of articulating surfaces but of unclear long term benefit.

Although very attractive as an option, the use of classic electrothermal chondroplasty devices may cause significant thermal damage to articulating surfaces and unacceptable level of irreversible chondrocyte injury. However, new devices are based on low-temperature radiofrequency technology which keeps operating temperatures below 50 degrees C and which are particularly suitable for use on Grade II and III chondromalacia. Grade II lesions are characterized by loose or fibrillated cartilage. For these lesions, the goal of the surgery is to remove the unstable, superficial layer and contour the cartilage surface. Grade III lesions are partial thickness lesions characterized by fissuring, unstable borders, and disruption of underlying chondral architecture. For these lesions, the goal of the surgery is to stabilize the edges of the lesion. This is accomplished by removing tissue layer by layer until a stable cartilage rim is reached, thus preserving the maximum amount of healthy tissue.

The microfracture and subchondral drilling cartilage repair techniques generate fibrocartilage cover of the defect, and more advanced autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) has a potential to repair defects in patella articulating surfaces (for more information about articular cartilage repair please see Articular Cartilage page).

|

|

|

Soft patella cartilage |

Fibrillar patella cartilage |

Patella Maltracking

Maltracking refers to several different conditions when the patella does not remain within the central groove of the femur (thigh bone). This includes ELPS (excessive lateral pressure syndrome) or LPCS (lateral patellar compression syndrome), patella tilt, subluxation and dislocation. The kneecap most commonly tends to tilt and glide towards the outside of the knee (subluxation). The patella may slip outwards and stay there, in which case the knee will lock and you will not be able to straighten it. Most of the time patella will reduce itself spontaneously, if you manage to relax a bit, but sometimes this memorable experience will require manual reduction by yourself, another person or a casualty officer in the A&E department. In most cases of recurrent patella dislocation several anatomical conditions are frequently seen: relatively flat patella, patella alta (high-riding patella), shallow femoral trochlea, femoral torsion, loose medial structures, general joint laxity, etc.

|

|

|

Lateral patella dislocation |

Stable, subluxed and dislocated

patella |

Traumatic Patella Dislocation

Patients who have acute patellar subluxation or dislocation generally

present with an episode of instability and have localised tenderness

along the medial extensor retinaculum or possibly at the adductor tubercle,

which is the origin of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL). Also,

the patient has localised tenderness along the peripheral edge of the

lateral femoral condyle where impaction from the patella occurs with

flexion of the knee. An effusion (haemarthrosis) is often present. Radiographs

should be obtained, since up to 20% of patients develop osteochondral

loose body secondary to patella dislocation. Patients may develop mechanical

locking symptoms which may require arthroscopic surgery. Acute patellar

subluxation often appears no different from an acute dislocation. With

a dislocation, the patient reports that the kneecap moved out and had

to be pushed back into place. With subluxation, the patient reports

that the kneecap slipped out, then went back into place spontaneously.

In patients treated non-operatively for an initial episode of patellar

dislocation, the chance of recurrent dislocation ranges from approximately

15% to 44%. Patients who have spontaneously reduced patella dislocations

are more prone to recurrent dislocations, but they seem to have no evidence

of long-term degeneration of the patello-femoral articulating surfaces.

If dislocated, the patella should be reduced and the knee should be

immobilised initially in 300 of flexion with a long hinged knee brace.

Plaster cylinders should not be used for immobilisation. There are controversies

regarding indications and timing for surgical treatment of acute dislocation

and chronic recurrent dislocation. The main concern in the long run

is the repetitive damage to patellofemoral articular cartilage.

tubercle,

which is the origin of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL). Also,

the patient has localised tenderness along the peripheral edge of the

lateral femoral condyle where impaction from the patella occurs with

flexion of the knee. An effusion (haemarthrosis) is often present. Radiographs

should be obtained, since up to 20% of patients develop osteochondral

loose body secondary to patella dislocation. Patients may develop mechanical

locking symptoms which may require arthroscopic surgery. Acute patellar

subluxation often appears no different from an acute dislocation. With

a dislocation, the patient reports that the kneecap moved out and had

to be pushed back into place. With subluxation, the patient reports

that the kneecap slipped out, then went back into place spontaneously.

In patients treated non-operatively for an initial episode of patellar

dislocation, the chance of recurrent dislocation ranges from approximately

15% to 44%. Patients who have spontaneously reduced patella dislocations

are more prone to recurrent dislocations, but they seem to have no evidence

of long-term degeneration of the patello-femoral articulating surfaces.

If dislocated, the patella should be reduced and the knee should be

immobilised initially in 300 of flexion with a long hinged knee brace.

Plaster cylinders should not be used for immobilisation. There are controversies

regarding indications and timing for surgical treatment of acute dislocation

and chronic recurrent dislocation. The main concern in the long run

is the repetitive damage to patellofemoral articular cartilage.

Nonsurgical Treatment and Rehabilitation

Nonoperative management for patellofemoral instability involves maximizing lower-extremity strength and function. Patellofemoral instability symptoms may be reduced in some patients with the patella cut-out brace, which is thought to improve patellar tracking by stabilizing the patella within the groove. A secondary advantage of these braces is a warming effect on the muscle, which can improve muscle functioning and firing. Patella taping, or McConnell tape technique, was originally reported to have a high success rate in reducing patellofemoral pain and pain as a result of malalignment and/or instability, but subsequent researchers have been unable to reproduce the results of McConnell’s original study.

However, it is the opinion of most physiotherapists treating patellofemoral pain and instability that patella bracing or taping can be helpful adjuvants to a mainstay of patellofemoral rehabilitation. A more recent approach to patellofemoral instability is that of going farther up the kinematic chain and involving the relationship of the femur to the pelvis. Patella bracing and McConnell’s original taping technique advocate trying to control the relationship of the patella to the femoral trochlear groove as a strategy to treat patella instability. Several brace companies offer patellofemoral bracing products designed to address patella instability. An alternative approach would be to recognize that femoral rotation needs to be controlled underneath the patella, and this is largely controlled by the pelvifemoral musculature, in particular the muscles that control hip rotation. Therefore, an attempt to maximize strength of the pelvifemoral musculature, including hip extensors and hip abductors, is emphasized. In addition, an anteriorly rotated pelvis or hemirotated pelvis is a common postural habit of many people with patellofemoral pain syndrome. This can aggravate patellofemoral instability by posturing the femur in internal rotation (which is a coupled motion associated with an anteriorly tilted pelvis) and placing the pelvifemoral musculature in a nonoptimized biomechanical position.*

Corrective Surgical Procedures

|

|

| Arthroscopic electrothermal

lateral release |

Arthroscopic Lateral Release: this day-case arthrosopic surgical procedure may be used to divide the lateral retinaculum (the soft tissue which pulls the patella towards the outside of your knee). It is performed in order to reduce this pull and therefore to centralise the patella, in people with patellofemoral pain combined with patella tilt. This simple procedure is not effective for most patellofemoral problems and in some cases it may make things worse, in terms of discomfort, pain and swelling. Most surgeons would recommend that a lateral release be used only when there is residual patella tilt, which is a physical examination sign of a tight lateral retinaculum. As it is very important that you fully understand the goals and potential complications of this simple procedure, please discuss this operation in detail with your surgeon. Sometimes, if the pain or bleeding can not be controlled well enough before you are discharged home on the day of your surgery, we prefer to keep you in the hospital overnight.

Patella Stabilisation: historically, surgical procedures to stabilize the patella involved an advancement of the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) portion of the quadriceps muscle in an effort to dynamically prevent the kneecap from dislocating laterally. This could be done in isolation as a muscle transfer, or with imbrication of the medial retinaculum, which forms the distal extent of the deep fascia of the VMO muscle. The clinical significance of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) has been demonstrated in a variety of recent scientific publications. These studies yield strong evidence that the MPFL provides a critical soft-tissue restraint against lateral patella translocation. A more modern approach to surgical stabilization of the patella is to reestablish a medial soft-tissue restraint by repairing or reconstructing the MPFL, which is quite difficult in chronic cases. Only this surgical procedure restores normal passive limits of the patella against lateral translation. It is believed that the MPFL is the essential ligament to be restored to a suitable tension or length after acute lateral patella dislocation, but there continues to be debate on how to accomplish this goal. *

Following patella stabilisation surgery your knee will be in a long, hinged, brace for approximately six weeks. During this period the amount of knee flexion i.e. knee bend will be limited stating at 30 degrees and adjusted by 10 to 15 degrees each week, whilst attending physiotherapy. In addition you may also require elbow crutches to mobilise. The physiotherapist will progress your exercises and you will gradually be allowed to fully bend the knee. After six weeks you will be reviewed in clinic and if everything is satisfactory you may be allowed to discontinue wearing the brace.

Other Patellofemoral Conditions

|

|

| Arthroscopic view of enlarged

and torn plica |

Plica bands are folds of synovial membrane within the knee that are normal anatomical structures in most people. However, if the knee is injured then they can become painful, as they rub against the thigh bone. As the knee bends and straightens you can usually feel a thickened band, especially if it is enlarged or torn. Most plica bands do not cause any problems, but rarely enlarged and hard band may require arthroscopic excision.

Patella tendinosis is a common clinical condition seen in sports medicine. Numerous investigators worldwide have shown that the pathology underlying these conditions is tendinosis or collagen degeneration. Painful overuse tendon conditions have a non-inflammatory pathology and therefore tendinitis is not a correct term. The usual complaint is pain well-localised at or near the inferior pole of the patella. It frequently affects people who use their knee extensor mechanism in a repetitive manner in "explosive" extension or eccentric flexion such as that in basketball, volleyball, or dancing. However, it may occur in athletes participating in other sports such as running, football, tennis or gym-training. This condition was first described as "jumper's knee". For more information on this condition please see Overuse injuries page.

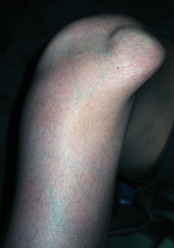

Prepatellar Bursitis: plumbers, carpet layers, roofers, gardeners and other people who spend a lot of time on their knees often experience swelling in the front of the knee. The constant friction irritates a small lubricating sac (bursa) located just in front of the kneecap (patella). The bursa enables the kneecap to move smoothly under the skin. If the bursa becomes inflamed, it fills with fluid and causes swelling at the top of the knee. This condition is called prepatellar bursitis. Usual symptoms are:

- Pain with activity, (but not usually at night)

- Rapid swelling on the front of kneecap, which also becomes tender and warm to the touch

Conservative treatment is usually effective, as long as the bursa is simply inflamed and not infected. Try the following:

- Rest and discontinue the "offending" activity until the bursitis clears up

- Apply ice at regular intervals three or four times a day for 20 minutes at a time

- Elevate the affected leg except when necessary to walk

- Take an anti-inflammatory medication

If the swelling is significant, your GP may decide to drain (aspirate) the bursa with a needle. Chronic swelling that causes disability may also be treated by draining the bursa, but if the swelling continues, your orthopaedic surgeon may recommend surgical removal of the bursa. The operation is an outpatient procedure. It takes a few days for the knee to regain its flexibility and some weeks before normal activities can be resumed.

* Source: Elizabeth A. Ardent, MD. Management of Patellofemoral Disorders. Orthopedic Special Edition 2001 (7) 2.

Patella Alta and Patella Baja (Infera)

How do we establish if the patella is too high or too low? The objective of this study on 245 patients was to determine the range of the patellar tendon length to patellar length ratio on MRI of the knee in order to aid in the establishment of MRI criteria for patella alta and baja. Patellar length (PL) and patellar tendon length (TL) were measured by a single musculoskeletal radiologist on sagittal images by a line connecting the superior and inferior patellar poles and the shortest length of the inner margin of the tendon respectively. TL/PL ratio was subsequently calculated. The distribution of ratios was evaluated; the extreme 2.5% at each end of the distribution was defined as patella alta and baja. The authors of this study also found that females had significantly higher TL/PL ratio than males (1.0878 and 1.0032 respectively). Ratios defined for patella alta and baja were 1.52 and 0.79 respectively in females and 1.32 and 0.74 respectively in males ( p<0.0001). The authors conclude that Patella Alta is determined as TL/PL of more than 1.50 and Patella Baja is determined as TL/TP of less than 0.74, somewhat different than traditionally quoted radiographic and previously described MRI criteria.

in order to aid in the establishment of MRI criteria for patella alta and baja. Patellar length (PL) and patellar tendon length (TL) were measured by a single musculoskeletal radiologist on sagittal images by a line connecting the superior and inferior patellar poles and the shortest length of the inner margin of the tendon respectively. TL/PL ratio was subsequently calculated. The distribution of ratios was evaluated; the extreme 2.5% at each end of the distribution was defined as patella alta and baja. The authors of this study also found that females had significantly higher TL/PL ratio than males (1.0878 and 1.0032 respectively). Ratios defined for patella alta and baja were 1.52 and 0.79 respectively in females and 1.32 and 0.74 respectively in males ( p<0.0001). The authors conclude that Patella Alta is determined as TL/PL of more than 1.50 and Patella Baja is determined as TL/TP of less than 0.74, somewhat different than traditionally quoted radiographic and previously described MRI criteria.

- Source: Shabshin N et al: MRI criteria for patella alta and baja. Skeletal Radiology, August 2004, 445-450.

A Few Words About Semantics and Orthopaedic Terminology

The term Patella Baja, or lower patella, was coined by Drs James M Fox (from South California Orthoedic Institute, www.scoi.com), Martin Blazina and John Jurgutis in 1973, as a reference to California and its Spanish history (geographically Baja California, or lower California, is at the southern border with Mexico). This term has been accepted and is well known in orthopaedic and sports medicine literature, although the term Patella Infera would be more consistent with the term Patella Alta, as an opposite condition.

- For more information see: www.carletonsportsmed.com/patbaja.htm

Further information on patellofemoral problems:

- The Patellofemoral Foundation: http://www.patellofemoral.org

- William R. Post, MD. Patellofemoral Pain: Let the Physical Exam Define Treatment. The Physician and sportsmedicine, January 1998.

- Scott A. Paluska, MD; Douglas B. McKeag, MD, MS. Using Patellofemoral Braces for Anterior Knee Pain. The Physician and sportsmedicine, August 1999.

- Mark S. Juhn, D.O. Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Review and Guidelines for Treatment. The American Academy of Family Physicians.

-

Patrick J Potter, MD, FRCP(C). Patellofemoral Syndrome. eMedicine, March 16, 2006.

Further information on patellofemoral exercises:

- Mark S. Juhn, D.O. Exercises for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. The American Academy of Family Physicians, 1999.

- Shannon Erstad, MBA/MPH. Exercises for patellar tracking disorder. Healthwise, February 14, 2008.

- Jordana Bieze Foster. ACSM 2009: Exercise Improves Patellofemoral Pain. Medscape Medical News, May 29, 2009.

CKC Downloads:

This page was updated on: 13 May 2018

Site last updated on: 28 March 2014

|

[ back to top ]

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.